Escaping the Dark Forest

On September 15, 2020, a small group of people worked through the night to rescue over 9.6MM USD from a vulnerable smart contract. This is our story.

I was about to wrap up for the night when I decided to take another look at some smart contracts.

I wasn’t expecting anything interesting, of course. Over the past few weeks I had seen countless yield farming clones launch with the exact same pitch: stake your tokens with us and you could be the next cryptocurrency millionaire. Most were simply forks of well-audited code although some tweaked bits and pieces, sometimes with catastrophic results.

But amidst all of the noise there was some code I hadn’t seen before. The contract held over 25,000 Ether, worth over 9,600,000 USD at the time, and would be a very juicy payday for anyone who managed to find a bug in its logic.

I quickly looked through the code for where Ether is transferred out and found two hits. One of them transferred the Ether to a hardcoded token address, so that could be ignored. The second was a burn function that transferred Ether to the sender. After tracing the usage of this function, I discovered that it would be trivial for anyone to mint tokens to themselves for free, but then burn them in exchange for all of the Ether in the contract. My heart jumped. Suddenly, things had become serious.

Some digging revealed that the contract I had found was part of Lien Finance’s protocol. Unfortunately, their team was anonymous! The only IM platform they supported was Telegram, and I couldn’t be sure that the admins of that channel were actually protocol developers or just a few early supporters. The last thing I wanted to do was accidentally leak the exploit to the wrong person.

After browsing their website a little while longer, I noticed that they had worked with ConsenSys Diligence and CertiK for an audit. This seemed like a good avenue, since both ConsenSys and CertiK must have interacted with the developers during their audits. I quickly pinged maurelian on Telegram.

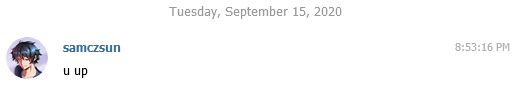

Unfortunately, time ticked on, my heart kept pounding, but there was no response from maurelian. It seemed like he had already gone to sleep. Desperate, I sent a message to the ETHSecurity Telegram channel.

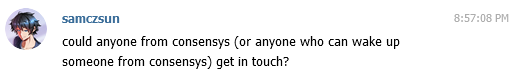

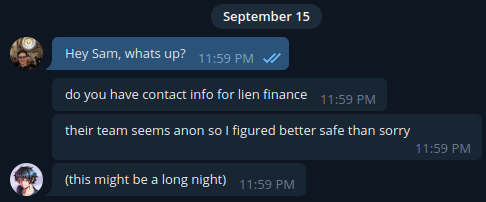

Within minutes, I got a message from someone I’d worked with quite a few times in the past - Alex Wade.

My head had just hit the pillow when I got a knock on my door. It was my roommate: “Sam’s in the ETHSec Telegram asking for anyone from Diligence.”

Knowing Sam, this couldn’t be good. I found a channel we’d set up with Lien a few months ago and an email address. Better than nothing, given their team was anon.

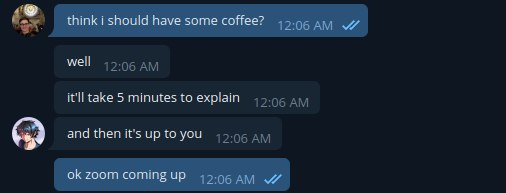

I was still half asleep. Sam, not wanting to commit details to text, asked for a Zoom call. Groggily wishing I was back in bed, I attempted to gauge the severity of the situation:

Sam and I reviewed the code together. By this point, Sam had already prepared a sample exploit and was able to confirm the issue on his machine. The conversation quickly turned to discussing options:

- Attempt to exploit the issue ourselves.

- Reach out to Lien and have them go public, urging users to withdraw.

Neither of these were appealing options. The first was risky because, as discussed in Ethereum is a Dark Forest by Dan Robinson and Georgios Konstantopoulos, the possibility of our transactions getting frontrun was very real. The second option was similarly risky, as a public announcement would draw attention to the problem and create a window of opportunity for attackers. We needed a third option.

Recalling a section from Ethereum is a Dark Forest, Sam reached out to Scott Bigelow:

If you find yourself in a situation like this, we suggest you reach out to Scott Bigelow, a security researcher who has been studying this topic and has a prototype implementation for a better obfuscator.

After participating in the recovery attempt from Ethereum is a Dark Forest, which ultimately lost to front-runners, I was hungry for a re-match. I’ve spent time monitoring front-running and designing a simple system that seemed able to fool generalized front-runners, at least for the $200 I’d been able to test it with. When Sam reached out to me in the late evening with the innocent-sounding “mind staying up for another hour or so”, I couldn’t wait to try it out! I was already working it out: how I’d make a few tweaks, stay up a couple hours, feel a sense of accomplishment having helped rescue and return a few thousand dollars of user funds, and get a good night’s sleep.

Those plans immediately fell apart when Sam shared the contract with me: ~25,000 ETH, valued at $9.6M, at stake. For as much as I wanted that rematch, $9.6M was way outside my humble script’s weight class.

For the past few months, I had been trying to establish contacts with miners for this very purpose: white-hat transaction cooperation. If ever there was a time to appeal to a miner to include a transaction without giving front-runners the chance to steal it, it was now. Luckily, Tina and I have worked together over the past few months on establishing this cooperation. It seemed like a slim chance at the time, but it was worth a shot: let’s bring Tina into the rescue attempt to work with a mining pool to mine a private transaction.

I had just evacuated from the Bobcat forest fire and was sipping on unknown beachy drinks zoning out to the monotonic sound of dark Pacific waves, when a Telegram DM from Sam buzzed me back to a darker reality: “funds at risk, frontrunnable”. Over the last few weeks, I had been collaborating with Sam and Scott on a research project on MEV and could already guess their ask before they sent it: a direct channel to shield a whitehat tx from getting sniped by the “advanced predators” in the mempool’s “dark forest”.

Since this was a risky move that entailed exposing our strategy to miners, we decided we should first try to get the greenlight from the anonymous Lien team. While Alex was trying to get in contact via ConsenSys-internal channels, we tried to loop in CertiK as well.

I realized it may take another 4 hours before Certik's US-based auditors would wake up, yet the clock was ticking. Knowing nothing much about CertiK beyond the fact it had serviced quite a few Asian projects, I tried to reach the CertiK China team to arbitrage the time zone difference. I blasted a casual sounding message in “DeFi the World” and “Yellow Hats” WeChat groups. Four leads slid into my DMs independently within 30 minutes, confirming the WeChat ID that I connected with was indeed the real Zhaozhong Ni, CTO of CertiK. I was added to a WeChat group with 5 CertiK team members, yet at this point I was still not in a position to disclose the project nor the vulnerability. To minimize the exposure and potential liability, we could only invite one member from Certik to join our whitehat operation. After passing a final verification via official email, Georgios Delkos, the engineering lead at CertiK joined our call.

With Georgios’s help, Alex was able to quickly get in contact with the Lien team and verify their identity. We brought them up-to-speed on the current situation and asked for their permission to try working directly with a mining pool to rescue the vulnerable funds. After some deliberation, the Lien team agreed that the risk from trying to rescue the funds directly or publishing a warning was too high, and gave the go-ahead to continue.

Now we needed to identify a mining pool that had the infrastructure ready in place and would be willing to cooperate with us ASAP. Which mining pool should we tap? Which contact from the pool would be in a position to make technical decisions swiftly that help us beat the clock?

SparkPool came to mind, as I knew they had been working on a piece of public infrastructure called Taichi Network that could easily offer what we needed. I decided to ping Shaoping Zhang, SparkPool’s co-founder, who had helped me investigate mempool events in the past.

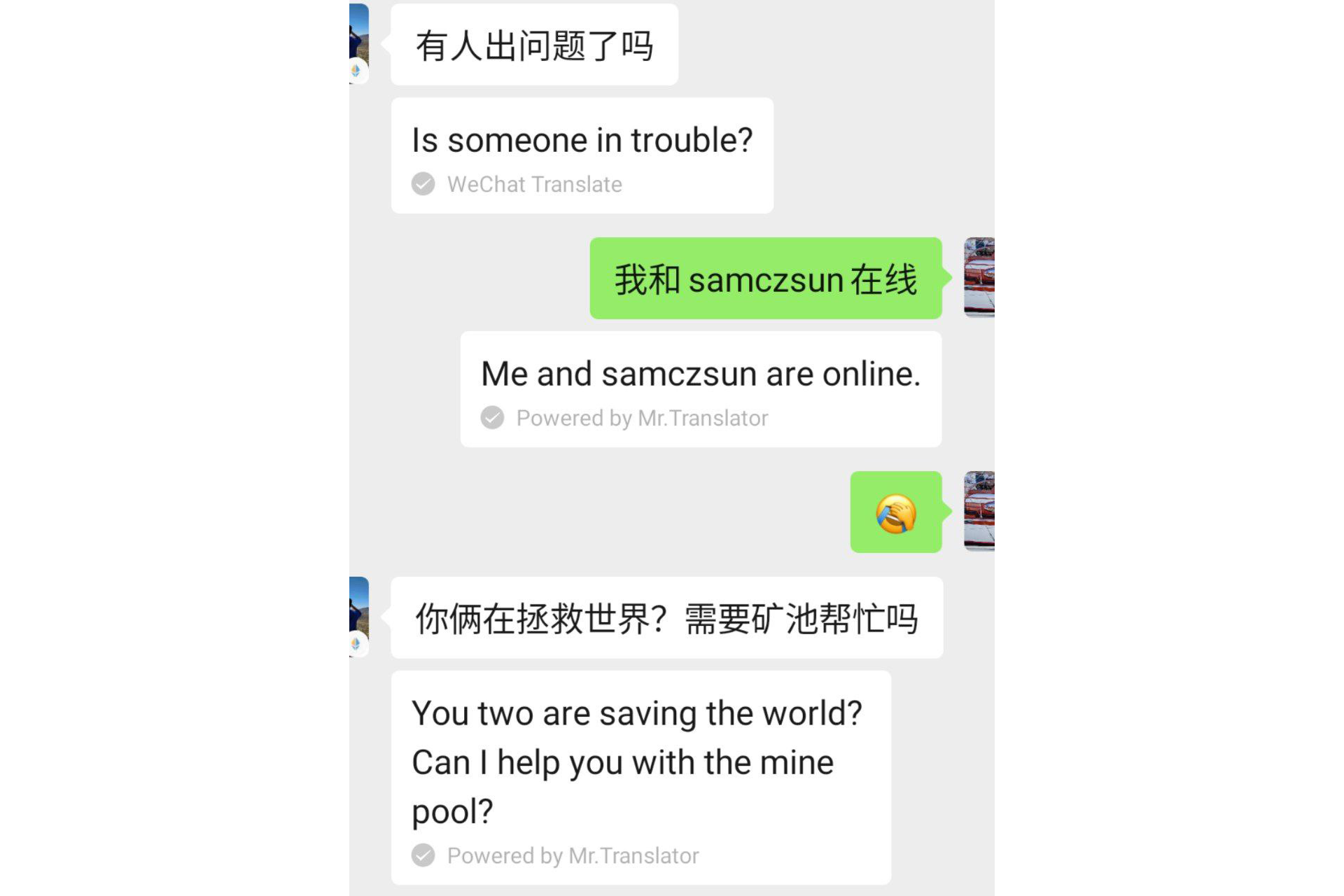

Half an hour later, Shaoping responded: “You mean do we have a whitelist service for transactions? Sorry, we don’t.” Oops, something was lost in translation, “whitehat” and “whitelist” sounded similar in Chinese.

“There’s 10mn dollar worth of funds at risk. samczsun is on the line.” I tried again to communicate the situation without revealing any specifics.

“Are you guys saving the world again? Do you need help from our mining pool?” To my surprise and great relief, Shaoping jokingly extended an offer to help. After official email verification, Shaoping popped into our marathon Zoom call with the support of a roomful of SparkPool devs.

After lunch, just when I was about to take a nap, I received a message from Tina: “Has SparkPool ever helped with whitehat transactions??” I mistook it for whitelisting a transaction at first. No whitehats had approached us before, and we were not familiar with what “whitehat transactions” entailed. After Tina explained it in more details, I realized that what they needed was a private transaction service, i.e. the whitehats wanted to send transactions to save a DeFi contract, but in order to prevent getting front-runned, they needed a mining pool to include the transaction without broadcasting it.

We had been working on a “private transaction” feature on our Taichi Network, which was still under development and had not been tested. I brought the whitehats’ request to our development team, and explained the urgency: our private transaction feature needed to be in production within a few hours. Our devs said they could try their best to finish in time, and we immediately got to work. We finished development of the private transaction feature in 2 hours, and then spent some time fixing bugs.

After we completed our internal testing, we sent the whitehat.taichi.network endpoint to Scott Bigelow to deliver the whitehat payload.

While SparkPool was working to deliver this brand new whitehat API, Sam and I were finishing the script to generate 4 sequential signed transactions. Processing these transactions in order would not withdraw the ~25,000 ETH itself, but would transfer 30,000 SBT+LBT tokens (which were “falsely” created) to the Lien team, allowing them to submit the final transaction to convert these tokens back into ETH. By transferring the infinitely mintable SBT+LBT tokens to Lien instead of ETH, we used more transactions to obscure how the attack worked from generalized front-runners (in case of a re-org), and I was able to avoid incurring $9.6M of income, even if for a moment.

Once we had generated 4 signed transactions, Sam and I spent a long time verifying their combinated behavior using a variety of multi-call transaction simulation tools. These 4 transactions, less than 1.5KB of data in total, were ready to heist $9.6M of assets, so long as no-one but SparkPool sees them until it is too late.

I tested SparkPool’s whitehat endpoint with a meaningless transaction, and it worked exactly as expected: the transaction was not seen in the mempool, then suddenly appeared as part of a SparkPool block! It was like watching water vapor turn directly into ice without that pesky liquid phase.

After adapting the transaction-creation script to feed the transactions directly to SparkPool’s new endpoint, it was time. I hesitated for a moment, but this was absolutely our best effort. We might lose $9.6M, but there would be no regrets: I hit “run” in IntelliJ. I’m not sure why, but I expected it to take a while, like node would understand the gravity of the situation and take its time. It did not; the transactions were sent in a matter of milliseconds.

Everyone on the call began refreshing Etherscan with such vigor, I wondered if the Etherscan team would see a 3-minute spike in traffic. Since only SparkPool had the transactions, and only a portion of SparkPool’s hash rate was dedicated to this purpose, there was nothing to do but sweat and wait. Each block that appeared from another miner mocked us. Someone on the call would announce the miner to nervous chuckles. The ~15 blocks it took before our transactions were included felt like hours, but finally, we had our immaculate transactions: mined, in order, not reverted.

We watched with relief as more and more blocks were built on top of ours and our concerns about block re-orgs quickly faded. The Lien team was now in possession of enough SBT+LBT tokens to liquidate their entire system, and Sam went to coordinate the final phase of the rescue.

Now that we had successfully transferred the tokens to Lien and there was no sign of any frontrunning, attempted or otherwise, we quickly pinged them with the good news. They confirmed that they received the tokens and immediately sent out a transaction to withdraw the bulk of the ether stored in the contract. Seconds later, a pending transaction appeared on Etherscan.

As we watched the loading indicator spin, I took the opportunity to reflect upon the events that lead to this moment. What had started as a quick glance at some contracts ended up turning into full-blown warroom that pulled in experts from around the world. Without Alex and Georgios, we wouldn’t have been able to make contact with the Lien developer. Without Scott, we would’ve been going into a rescue blind. Without Tina, we wouldn’t have been able to get in contact with CertiK or SparkPool. Without SparkPool, we would’ve been doomed to repeat the history that Dan had written about just weeks ago.

And yet on a late Tuesday night, our unlikely group united under a common cause and worked tirelessly to try and ensure that over 9.6 million dollars would be returned to their rightful owners. All of our efforts over the last 7 hours led to this single pending transaction and the spinning dots that came with it.

When the loading indicator finally turned into a green checkmark, the tense silence on the call gave way to a collective sigh of relief.

We had escaped the dark forest.

This post was the culmination of the hard work of many people. Special thanks to Alex Wade, Scott Bigelow, Tina Zhen, Georgios Delkos, and SparkPool for being there when the ecosystem needed you most, as well as Alex Obadia and Dan Robinson for reviewing this post and providing feedback.

If you’re interested in the technical details behind the exploit, click here to learn more. If for some reason you still haven’t read Ethereum is a Dark Forest, you should definitely do so too.

[1] The transaction